Introduction1

This book has big dreams, and wants you also to dream—not just the familiar nighttime adventures with your soul, but to dream all-the-time adventures with what-is-possible. This book also hopes to inspire you to imagine—that is where the future begins. For me, imagining begins with questions, the greatest invention language users came up with for opening themselves to new futures.

Movies have brought the imaginings of a few creative people to life for billions of others. In that way, movies have great power. Some have shown us nightmares, apocalypse, war. Is that the kind of future we want to imagine for ourselves and then bring to life?

Do you remember going to 3D movies where you‘d put on the dorky blue-and-red glasses (think about that symbolism with regard to current politics!) with which you were able to see a whole extra dimension leaping out of the screen at you? This book wants to be those glasses for us, except for one difference—s/he/we/it wants us to be able to see not just an enhancement—something that’s already there in 2D—but rather something that we haven’t been able to see before.

The previous paragraphs, starting with the first sentence, are grounded in a category mistake according to current linguistic and cultural standards. We all know that books don’t have dreams, right? They’re inanimate. And why not just use “it” for the pronoun? By means of that same category mistake, we’re going to question the “it-ness” of some things. Poets and cartoonists do.

This book is not a thing. It might seem that way to you now, especially if you are holding a paper or digital facsimile in your hands. But this book is a being, a someone rather than a something; not a human being like you, but an idea being. Approach the book with curiosity, not fear; with playfulness, not certainty; as if you want to make a new friend.

This book loves you. Big category mistake, right? But what if every book on your shelf came into your life to be your friend, companion, intellectual sparring partner? What kind of world would we be living in then?

This book wants to be a springboard for you, for me, for all of us to dive into realms yet to be imagined. Dream. Imagine. Invent new ways to language a world of idea beings into existence. Let this book open that door for you.

The preceding text is what came to me when I asked what this book wanted to say by way of introduction. This type of active imagination, as Carl Jung called such dialogues with dream images and other entities, can be a useful way to bridge the realms of psyche and matter, to find the numinous in the mundane, the sacred in everything.

The Industrial Revolution and the mindsets and paradigms emerging from it exclude Life from matter. The developments from that revolution, which continued into the information revolution, helped to deliver us to where we are now—on the brink of a sixth mass extinction event, and in political and economic chaos, ill health, and facing global climate change. In other words, we are facing a crisis of crises, a metacrisis. This situation did not happen recently just because someone came up with a catchy name for it. Wise people have seen it coming for decades at the very least.

Any good systems theorist will tell you that technology cannot save us from the metacrisis and that there also needs to be a widespread mindset shift. A mindset is the totality of assumptions, beliefs, and knowledge that together form how one makes sense of the world. Often we simply adopt the mindsets of our parents or authority figures, and those reinforced by artificial-intelligence algorithms. Philosophers, physicists, and poets have been urging a change of mindset for decades now.

However, one thing that seems to have eluded the prophets of the past is how deeply embedded the current mindset is in the very structures of language[2]—not just the words, but the structures that shape how words can and cannot be combined. Although humanity has been through several mindset shifts in the past few millennia, they have all occurred within a set of assumptions foundational to language structures that have not changed (or have not changed much) during that time. Just as words have sets of assumptions associated with them, linguistic structures such as syntax and logic do too. Although that is not news to linguists, it seems to have eluded many people who seek to solve today’s problems by using the same mindset that created those very problems. Solving problems using the same mindset that created them is like trying to fix a leaky pipe by using a tool that causes more leaks.

How do we extricate ourselves from such a vicious cycle? Because both the problem and potential solutions are expressed in language that shares the same underlying assumptions, to shift the mindset we must also shift, alter, or invent novel forms of language that will enable us to express a new mindset, one grounded in a different set of assumptions. That is the insight this book presents, as a possibility for all of us to take up.

It does not work to try to express wholeness, for example, by using language structures that reify separateness. It does not work to try to bring peace by using metaphors that call to mind war. If we want to regenerate living systems, it will not work to continue treating them as “it” rather than “we.” We humans will need to invent new forms and structures for all the interdependent aspects of language, not only words and syntax but also semantics, logic, category structure, and culture.

I do not propose an answer or solution—intentionally, because language is a phenomenon of the collective. Neither I nor any individual can do it alone, as language requires agreement among users in order to be useful. Instead, I ask a lot of questions. I want you to examine your own and your society’s heretofore unexamined beliefs and assumptions. I hope that this book helps you uncover assumptions you didn’t know you had.

The book is structured as a journey. Much like a drive across country, we will only stop at certain places—important historical sites, beautiful vistas, good restaurants. For example, while I was on a trip across Canada several years ago, one memorable stop was at a park that provided a view of a fascinating train tunnel. The train entered the tunnel at a low elevation, made a complete loop inside the mountain, and emerged at a higher elevation, above the back end of the train. If the train was long enough, you could see both the front end at one elevation and the back end at a different elevation simultaneously. Sometimes our journey might seem like that, like going into the tunnel and then stepping out to see both ends of the tunnel, and in your imagination seeing through the mountain. Here is the itinerary.

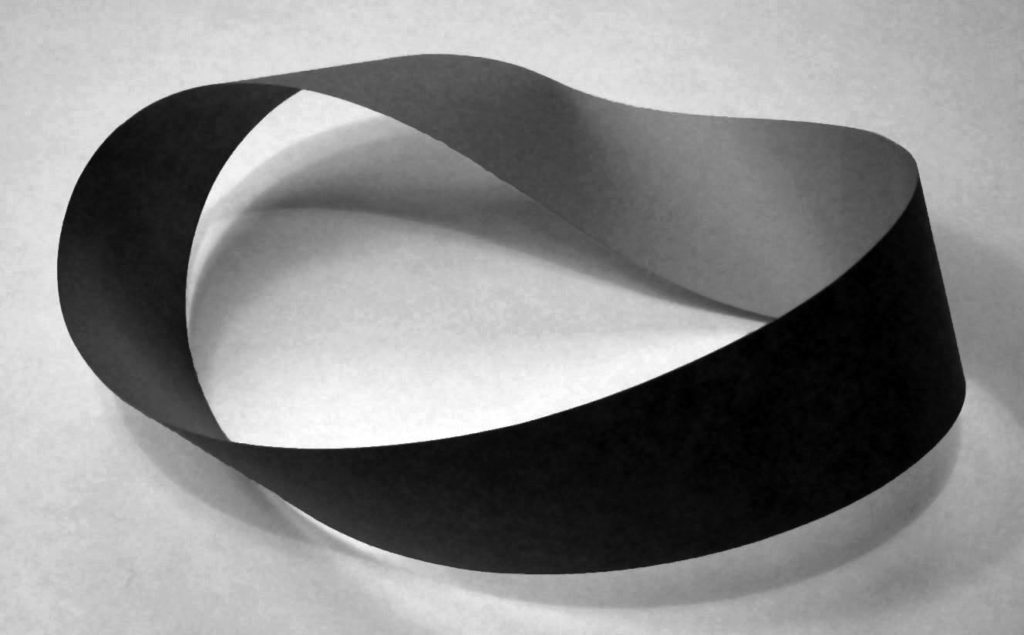

First, some important cognitive foundations for the rest of the book are introduced, namely, the curious topological structures of the Möbius strip and the Klein bottle. They also serve as a map, of sorts. Their paradoxical nature is key to understanding the relationships among many topics of this book, particularly language and consciousness (Chapter 1). Another paradoxical device, the kōan, is introduced and subsequently used throughout the book (this entire book could be likened to a long kōan) to snap you out of old, habitual ways of thinking. Kōans help one look at what is not there, at the hole in the whole (Chapter 2). To start the journey from where we are, we take stock of our “default” settings for being human (Chapter 3) and how we parse subjects, objects, and space (Chapter 4).

Other writers have suggested that to get someplace other than where the current mindset is taking us, we need to tell a new story about ourselves and our future. But can we tell a truly new story using the same old language structures? A new story requires not just new plots or new characters but radical shifts in what we think we are in relation to everything else. In Chapter 5, we explore how we might create language that expresses a radically new conception of ourselves in which we no longer leave our own evolution to chance, as if we were a creature without creative power. Rather, how can we consciously shape our own evolving? In light of the relationship between language and consciousness, perhaps we can influence our own cultural evolution by using language differently or creating different language. For example, what might language be like if it does not reify the world into somethings? Might we be able to live in a world of someones (Chapter 6)?

In fact, each of our bodies is a galaxy of someones, as we are home to millions of microbes, each with their own will to live (Chapter 7). By seeing ourselves in different types of part/whole, whole/part, and whole/whole relationships, we can begin to see the connectedness across scales of magnitude and levels of organization. As our microbes are to us, perhaps we are to Earth, and as we are to Earth, perhaps Earth is to the Milky Way. Given such complexity, it becomes clear that existing language is not structured to handle multiple scales and perspectives, not to mention the consciousness of symbiotes.

One way to see ourselves and our world differently—to shift perspectives—is by distinguishing our everyday “facet consciousness” from a more integral “diamond consciousness.” Such a shift not only alters our way of perceiving and but also shows us a profound way to question our assumption of separateness (Chapter 8). From there, we question how assumptions of separateness are embedded and embodied in the structure of language. A perspective grounded in either/or ways of thinking is then challenged by one that accounts for both/and as well as neither/nor. How can we build both/and and neither/nor into the structures of language (Chapter 9)?

To answer that question, it is necessary to look at how language functions as an invisible architecture of culture. As buildings provide structure and boundaries for physical spaces, language provides structure and boundaries for psychic spaces. However, because we use language mostly unconsciously, we fail to see how it structures our thinking, as well as everything else we use language to create, such as our laws, institutions, and relationships (Chapter 10). A simple example of a language structure that subtly influences our understanding of the world differently is the reflexive verb. Reflexive verbs illustrate a recursive relationship with oneself (Chapter 11).

Chapter 12 shifts our inquiry from what’s so to what could be so. If language has helped to keep us operating in facet consciousness, what would it take to expand language to enable us to operate from and communicate from diamond consciousness? For example, how might metaphors be revised to enable us to convey our interconnectedness (Chapter 13)? And how might we overcome difficulties in holding opposites in consciousness simultaneously (Chapter 14)?

Many spiritual and psychological leaders speak about wholeness, so in Chapter 15 we ask what it would take to speak from wholeness, and in Chapter 16 we begin to answer that question. We look specifically at the many of the facets of language that operate together, from words and syntax through logic and semantics to the category structures embedded in language by the culture that uses that language. After analyzing those aspects of language, I use an ancient Gnostic text to show an early attempt to express unity and wholeness using ordinary language. Next, by using Jean Gebser’s concepts of transparency and diaphaneity, we continue to examine that same text vis à vis integral consciousness and its expression in language (Chapter 17).

Chapter 18 addresses the growing community of people who enjoy inventing new languages. I hope to inspire not just conlangers but anyone interested in inventing new linguistic structures for expanding consciousness and better expressing complexity in existing languages.

The language-consciousness Möbial continuum comes full infinity sign now. Using Carl Jung’s descriptions of the psychic integrations (coniunctio) that occur in an individuating consciousness, I speculate on how similar integrations could occur in language. If consciousness and language are like two “sides” of a one-sided Möbius strip, then integration of consciousness could foster a concomitant transformation of the structure of language. As the users of language, we need to make that happen. I share my early, albeit inadequate, attempts to do that (Chapter 19).

Because our cultural institutions have their foundations in language and language is essential to all our activities, from thinking to governing to educating, even to marrying, in order to re-form (re-structure) cultural habituations that no longer serve us, it will be necessary to re-form the repository of their being, namely, the structure of the language by which we created them. To illustrate differences in assumptions, I provide examples of practices that are based on assumptions of separateness and others based on assumptions of profound interconnectedness (Chapter 20). Lastly, we must each confront the Big Question—Why? I share my why and ask you to consider yours. Mine is existential. We are facing a perfect storm of crises, not the least of which is climate weirding: CO2 stoked by the hurricane winds of artificial intelligence soaking us with retweeted memes, blinding us with dis/information that floods our screens and thunders through our communities, drowning democracy.

To continue playing the (infinite) game of life, let’s look at what has survived the test of time. Ancient wisdom, for example, emphasizes that both poles of a polarity are necessary and interdependent. For example, freedom requires responsibility; growth must be balanced by death; as above, so below. The old mystics used poetry and paradox to verbalize their visions of a both/and world. As a modern mystic, I propose to build both/and-ness into our language and consciousness, as they are Möbial, after all. From a both/and perspective, we can then expand into a more complex pluriverse, a multiperspectival world of many worlds.

To begin that process, I have put in the margins some glyphs that join opposite-pairs of concepts that are discussed in the accompanying text. They are not what I mean by “novel structures of language,” but they might inspire us to get there. For now, they are intended as a re-mind-er to hold interdependent pairs of polarities in mind simultaneously. It is a skill we must relearn. Because many such interdependent concepts have been separated and given distinct words, we have come to assume that they are ontologically separate when, in fact, they are inseparable. Need proof? Try exhaling without inhaling.

In our quest for new structures of language, let us not content ourselves with new content words or a new shade of meaning for a dilapidated concept. Let us not even look to new alphabets. Let us embrace our patterning instinct to its fullest extent to create entirely new forms and functions for language, because patterns activate our trans-rational capabilities. How can new patterns, both phonemic and graphic, enable us to express the heretofore unexpressible? (The inexpressible must remain silent, but there are plenty of experiences for which we simply have not yet conceived of expressions.) David J. Peterson, creator of many constructed languages (conlangs), sees the vast “uncharted territory” of what is possible to create linguistically. “The possibilities of what to encode and how to encode it are endless, and in about one thousand years of active language creation, we’ve barely scratched the surface of what’s possible.”[3] Our endeavor involves more than resuscitating desiccated concepts or reconstructing archeolinguistic structures; it involves resacralizing language and resacralizing the world.

Chapter 1

Welcome to the Möbius Strip Club

Forty years ago, Douglas Hofstadter’s book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid blew open my mind to pondering the mysteries of the paradoxical topological structures known as the Möbius strip and the Klein bottle.[4] Who needed drugs when you could get your neurons in a knot by listening to Bach and contemplating M.C. Escher’s prints?!

In the late 1800s, German mathematicians August Möbius described the Möbius band and Felix Klein described the Klein bottle, a higher-dimensional relative of the Möbius band. Those paradoxical structures gave me a way to model the both/and-ness I saw around me. A pendulum only goes back and forth from one extreme to another until it just stops. The same pendulum can be made to spin around in revolution after revolution, like seasons revolving in their appointed order, modeling cyclicity that doesn’t change. The Möbius and Klein structures, however, integrate opposites; hence, I use them because they embody paradox. In contrast to semantic paradox, such as “this sentence is false,” embodied paradox shows what it says. By embodying both/ands, such as inside and outside, these topological forms give us a way to represent complementarity and paradox, which will enable us to reform language to better express both/and-ness.

The Möbius Strip

The simpler structure, the Möbius strip, named after August Ferdinand Möbius (1790–1868), is a two-dimensional surface that requires three dimensions for its existence. A two-dimensional flat plane could exist in a two-dimensional space; however, because the Möbius surface has a twist in it, it requires three dimensions in order to exist. In other words, it’s a plane surface that is not flat. The twist adds a dimension, but that is not all it does.

Although it is constructed from a plane, like a piece of paper that has two sides, the Möbius strip has only one side. Locally, that is, at any point on the plane, it seems to have two sides. However, when you consider the entire surface globally, there is only one side.

To make a model of a Möbius strip, take a piece of paper that is longer than it is wide. (You can cut off a half-inch-wide strip from the last page of this book.) Join the narrow ends together, like you are making a loop, except give one end a half twist just before you join it to the other end. Then tape the ends together. As a result of the half twist, the Möbius strip has only one side and one edge.

Test it for yourself by drawing a line down its center until you return to your starting point. Did you ever cross an edge? Or, hold the edge of a Möbius strip against the tip of a felt-tipped pen. Color the edge of the Möbius strip by holding the highlighter still and rotating the Möbius strip around. You were able to color “both” edges without lifting the pen, right? To reveal something completely different, cut the Möbius strip along the center line that you drew. You just made a lemniscate. Then draw a line down the center of the resulting band and cut along it. What happened?

The Klein Bottle

The Klein bottle was invented (or imagined) by Felix Klein (1849–1925), another German mathematician. If you had flat, stretchy material and glued together two Möbius strips along their edges, one with a left twist and one with a right twist, you would create a Klein bottle. It would take a bit of dimensional trickery because the Klein bottle is a three-dimensional surface that requires four dimensions. Because we don’t live in a four (spatial)-dimensional world, it is not as easy to imagine a Klein bottle as it is a Möbius strip. The twist that a Klein bottle makes results in it looking like it has to go through itself, like you’d have to cut a hole in the material it’s made of. However, that is not the case if we are not limited to three spatial dimensions and further limited by drawing the Klein bottle in only two dimensions. Think of the difference between the drawing above and a real Klein bottle as being like the difference between looking at the painting by Marcel Duchamp called “Nude Descending a Staircase #2” and seeing a full 3D holographic movie of a nude descending a staircase.[5]

Similar to the Möbius strip, the Klein bottle embodies a continuum that encompasses a seeming duality. It, too, is one continuous plane that twists by curling in on itself; hence, inside and outside are not distinctly bounded but are one continuous unity. I like to use the Klein bottle as a model for the unity of complementarity because by its very nature it requires a higher dimension that is not part of our everyday three-dimensional reality. It points to the mystery of our existence, to the existence of the unknown, the n+1 dimension. Although mathematicians describe the extra dimension needed for the Klein bottle not to self-intersect as another spatial dimension, topological phenomenologist Steven M. Rosen maintains that the extra dimension is the depth dimension, as described by the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, which is a psychophysical dimension. Unlike the three spatial dimensions, which Heidegger characterizes as pure exteriority (“outside-of-one-another”), the depth dimension is an interior dimension, the first dimension that contains all the others as well as itself. It is self-containing.[6] Thus, the depth dimension allows for the complementaries to co-exist, for the movement and flow of process, for the unification of inner and outer, of light and dark, of self and other. It allows for Möbial and Kleinian structures to be more than just mathematical curiosities. Indeed, the depth dimension provides a way to integrate matter and psyche. By bringing psyche into the picture in this way, we can begin to heal the old Cartesian split between mind and matter.

The Klein bottle shows how the labels of a duality or polarity are only labels of aspects of a whole that are not, in fact, separate. It exemplifies the concept of a merging continuum or union of opposites. It embodies the type of paradox that could be incorporated into language to be able to speak into being a world in which us and them; old and young; rich and poor; conservative and liberal; black, white, red, yellow, and brown are distinct but interdependent. Möbius strips and Klein bottles factor into the rest of this book in important ways—as signs that integrate a local context and a global (or higher-level) context, as ways of embodying both/and, and as a new type of linguistic container.

Let’s consider how we might create Kleinian linguistic structures. How does a Kleinian structure work? According to Rosen,

the Klein bottle, as a living symbol of integral consciousness (a ’four-dimensional sphere’), brings unity and diversity together in such a way that neither is deficient. In its deficient expression, ‘diversity’ amounts to mere atomization or fragmentation, with parts being disconnected from each other (as in the negative form of postmodernism). This is sheer discontinuity. In the deficient expression of ‘unity,’ we have a totalistic, monological uniformity. As I understand Kleinian integrality, it isn’t enough to have both atomistic diversity and totalistic unity complementing each other. Rather, unity and diversity must interpenetrate each other in the Kleinian fashion in which they are different yet, paradoxically, they are a unity. The simplest example of this is given in the way the sides of a Möbius strip flow completely together while retaining their distinctness.[7]

I use these topological forms to structure the journey through this book. First we start, like one of M.C. Escher’s ants, walking on the surface of the Möbius strip. As we walk, first we seem to be on the inside; eventually that same path then seems to be outside. Correspondingly, first we’ll talk about consciousness, and those discussions will flow into various aspects of language. After that we must leap up so that we can see the entire surface of the discussions, that is, how one side seems to be two sides, how language and consciousness seem to be different sides of the same coin. Apperceiving one’s perspective is a defining part of perceiving.

Logic Less Traveled

Complementary pairs such as being and becoming, reason and emotion, have been debated since the beginning of recorded philosophy as if one of the pair must win the debate because we do not have a convenient way of expressing the paradoxical unity of opposites as afforded by Möbial and Kleinian structures. From Parmenides and Heraclitus to Plato and Aristotle, polarities have been part of the Western philosophical cannon, albeit polarities that have been split into monovalent concepts.

To see the utility of uniting polarities into a bivalent concept, let’s examine the famous “becoming” claim by Heraclitus of Ephesus that all is in flux. Specifically, he said, “Into the same river we both step and do not step. We both are and are not” (fragment 81 [49a]). This aphorism is usually interpreted to mean that nothing in the world is fixed and unchanging from moment to moment. We might not be able to perceive the change macroscopically, but change is occurring. Heraclitus believed in the unity of opposites—not that they are the same but that they are inseparable—and that the “strife” of opposing forces is at the core of creativity and transformation. Thus, night is inseparable from day because of the temporal continuity from one to the other, and “disease makes health pleasant and good, hunger satiety, weariness rest” because it is not possible to know one fully without having experienced the other. In biology we see such opposing forces maintaining homeostasis and homeodynamics and thus life.

Modern scholars have advanced the interpretation of that fragment (i.e., it is not the same water each time you step into the river) to align more with our Möbial/Kleinian structure:

If this interpretation is right, the message of the one river fragment is not that all things are changing so that we cannot encounter them twice, but something much more subtle and profound. It is that some things stay the same only by changing [emphasis added]. One kind of long-lasting material reality exists by virtue of constant turnover in its constituent matter. Here constancy and change are not opposed but inextricably connected. A human body could be understood in precisely the same way, as living and continuing by virtue of constant metabolism—as Aristotle for instance later understood it. On this reading, Heraclitus believes in flux, but not as destructive of constancy; rather it is, paradoxically, a necessary condition of constancy, at least in some cases (and arguably in all). In general, at least in some exemplary cases, high-level structures supervene on low-level material flux.[8]

Hence, the unity of opposites is what balances constancy and change in an ongoing dance. If they were not united, we might not grow, or we might grow uncontrollably until we become too much to sustain ourselves.

Although Heraclitus never systematized his philosophy and all we have is a collection of fragments, several key ideas can be gleaned from them. First, for Heraclitus, dynamicity was not something to be explained; rather, it was explanatory of other things. Second, processes can form higher-order systems and can be measured. Third, he saw that dynamic alterations could be seen as fostering both change as well as “permanence” (as described above).

Other Greek philosophers developed opposing positions. Most notably, Parmenides developed a philosophy of stasis, centered in there being one Being, unchanging, that cannot be perceived with the senses. I can think or speak of a dog today and a different dog again tomorrow, and even though those events might or might not involve an actual dog, there is something eternal and unchanging about [dog] that allows me to reference it at different times and in different contexts. Aristotle argued that what is unchanging about [dog] is its “essence,” which makes things what they are and restricts the kinds of changes they can undergo. Indeed, a puppy will become a dog, but a dog will never become a cat or a tree.

Both Heraclitus and Parmenides dealt with paradox albeit in their own ways. Since then, much of Western philosophy, and hence the natural sciences that derive from it, are still somewhat locked in debates on being versus becoming, structure versus function, nature versus nurture—partly because current modes of logical thought follow in the footsteps of Aristotle. Is that why we in the West have mostly wanted the poles of a polarity to be independent of each other and for one pole to have supremacy over the other? Why do we need one concept to win the imaginary “fight” between the opposites?

In the East, this issue was handled quite differently. They saw the interdependence of one on the other, and they saw how one can become the other when pushed to its extreme. In China, the symbol for the ongoing dynamics of opposites is the taiji or yin-yang symbol ☯. Although, that symbol has been found in old European cultures, the better-known Western symbol is the ouroboros, the snake eating its tail. It is not quite as suggestive of the interpenetration of opposites as yin-yang. In indigenous cultures of the Americas, there is also the concept of quetzalcoatl, the plumed serpent, in South American cultures, and the heyoka, a contrarian, in North American indigenous cultures.

I have often wondered why English doesn’t have concepts like yin-yang, since there is evidence for the symbol’s existence in Western culture.[9] Why is there no systematic way to integrate the opposites in Western languages? I believe we must try. In what follows I make the intellectual case for building the interdependence of opposites into concepts themselves. Although I experimented with developing image-based paradoxical concepts in my previous book, The One That Is Both, I now realize that I cannot do it alone. No one person is capable of completely revising the structures of language, logic, and thought. Language is a phenomenon of the collective and as such requires agreement amongst its users. A new form of language will require the users—ourselves—to develop it together. Let’s do it consciously, with input from the unconscious.

More importantly, however, we humans have a curious resistance to new ideas. If you doubt it, look at the history of science. Many of today’s scientific truths were initially ignored, ridiculed, or dismissed until enough evidence confirmed them. In turn, they might fall to newer ideas in the future. In physics, for example, it was shown that light can be measured as both a wave and a particle simultaneously. In biology, with the ascendency of epigenetics, the nature/nurture debate is finally shifting from either/or to both/and.[10]

A language in which complementarities form a new type of concept will require new logics, new graphic structures, and ultimately, a new consciousness. It will not work to impose the ideas about language herein onto a consciousness that has not developed sufficiently to grok them. Hence, I treat language and consciousness as the “sides” of our Möbius strip wherein it seems like there are two sides, but there is only one. Which side you see, or both, depends on your perspective and on your ability to shift perspectives and hold the possibility of both.

Similar to opposites that define one another and hence cannot be separated from the other, pairs or groups of concepts, such as language and consciousness, also share an intertwined type of relationship. In fully functioning human beings, language cannot be separated from consciousness any more than one side of a piece of paper can be separated from the other side.[11] Unlike an ordinary piece of paper, however, language and consciousness more resemble the seemingly different sides of a Möbius strip that really are just one side.

Notes

[1] These essays were blog posts on my old website, Consciously Evolving Language. I intended for the website to be interactive and immediate, a way to get some ideas out there and engage with people in real time rather than assemble them in a book that would take years to publish. When the website crashed (from neglecting to upgrade WordPress—a warning to the lazy!), I decided to refocus it. Nevertheless, the ideas in these writings are perhaps more relevant today than when they were originally composed, mostly between 2010 and 2014. The later chapters, however, are derived either from articles that I published or presentations that I made. They tend to be more academic.

[2] When I use the term language, I can only refer to my native tongue, English. Some claims for English might also be true for its parent languages but not necessarily for others. Please evaluate any claims about language against what you know for your own language.

[3] (Peterson 2015)

[4] (Hofstadter 2000)

[5] This comparison brings up the temporal dimension, so it is not an exact comparison. Although later I emphasize the inherent dynamicity (“becomingness”) that the Klein bottle represents, it is not the linear time dimension that is portrayed either in Duchamps’ painting or a holographic movie. It is also important to remember that these structures are only models, and “models are always wrong, but some are useful” –George E.P. Box.

[6] (Rosen 2008), p. 49.

[7] Steven M. Rosen, personal correspondence.

[8] (Graham 2015)

[9] https://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.com/2018/02/yin-and-yang.html

[10] (Ørstavik 2018)

[11] In stroke victims and other neurologically damaged individuals, language capacity can be lost or diminished while consciousness is intact.